The Trap of Ideal Motherhood

Cover Website.jpg

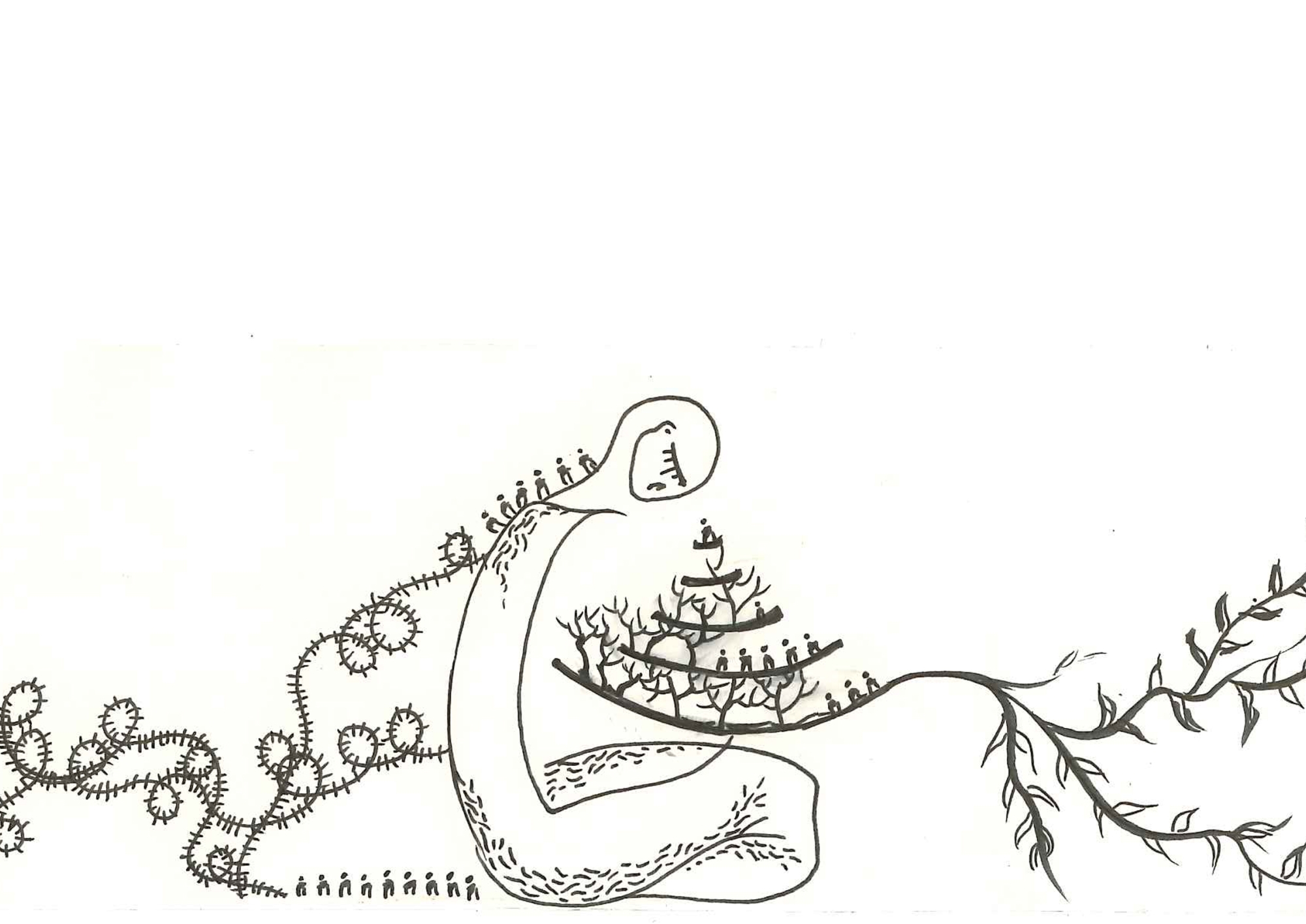

Illustration by Zeina Hamady 2018 ©

Mankind has always attempted to improve the human condition, working hard towards maximizing comfort in all aspects of life, such as mobility and shelter. Throughout the ages, perhaps these efforts have been most focused on facing nature’s forces and bending them to human whims and desires. In contrast, when it comes to women’s lives and physiologies, men are invested in maintaining the status quo. Despite the immense medical progress that may soon result in the creation of humans in laboratories, women are left to their sufferings when it comes to menstruation, and the hardships of pregnancy and childbirth.

For most people, motherhood is a sacred duty and honor that are bestowed on women alone, so they are expected to go through with it without seeking any kind of gratitude or appreciation in return. Society requires a workforce, and demands more reproductive labor of women, but does not pay attention to their need for improved conditions of care and birth. Instead, a ready-made, essentialist argument is always ready to spring: this is the fate and condition of womanhood since the beginning of times, so why complain?

The concept of women’s reproductive fate, a purely “feminine” burden, was reinforced by religions that worshipped fertility goddesses (like the Egyptian goddess Isis) and consecrated pregnancy and childbirth. The three monotheistic religions were particularly invested in this notion. In Judaism, for example, a woman is required to reproduce repeatedly in case one of those pregnancies happens to bear the Messiah who will restore the glory of the chosen people. For Christians, women are doomed to endure the recurring pains of childbirth to atone for the “evil femininity” they inherited from Eve, the original sinner. As for Islam, the hadiths that prompt men to marry fertile women who can birth an army of Muslims for the Day of Judgment abound.

Even outside of religions, and starting from the Renaissance era, many doctors and philosophers considered that women’s “natural” role was that of mothers, and that raising children was their primary (and only) responsibility. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was perhaps the most ardent advocate of this discourse, as his writings show, and he was joined by various studies that aimed to prove the centrality of the mother and her influence on all aspects of the her future children’s lives.

The French Revolution was a major actor that contributed in allowing the state to intervene in matters related to motherhood. In that context, the mother becomes the official symbol of the homeland (the Bust of Marianne); with the imagery of breastfeeding, she leads her disgraced people towards freedom.1 In addition to the labor of care work and childbirth, she is entrusted with educating the future “good” citizens of the Republic. Instead of participating in the political movement of the time, and despite their presence in the revolution, women were expected to be the mere transmitters of “patriotism” to their children, before sending them to the battlefields where they could fight for their homeland and values. Although women were told that motherhood made them as important as men, if not more, this was not translated into any tangible rights, as women’s legal situation remains the same. It is as if she has to be content with a sense of importance at being assigned a “noble” role men cannot fulfill.

Following World War I, governments increased their interest in mothers and children, as they needed them to rebuild their states and compensate for the devastating deaths. The traditional bourgeoisie, the church, and the state suddenly came together to bring back the women who had replaced men at work during the war, and veer them once more towards their “natural” role. Opposition to women working in factories increased, as it was alleged that it would jeopardize their reproductive health, leading to abortions, fetal deformities, and infertility. Governments put created entire programs that took care of mothers and their children through education and financial assistance, starting with schools, and going as far as instating celebrations such as Mother’s Day, and awards such as the medal of the ideal mother/family. Therefore, motherhood became recognized as work and respected by the community, but in return, women were not to expect remunerations, and had to do with moral recognition and symbolic acknowledgments. (I disagree with Silvia Federici’s proposal of remunerating motherhood as any other labor; instead, these norms must be dismantled from their roots).

Interestingly, it is within the same historical timeframe that philosophers and clerics attempted to vilify human instincts, attributing them to vice and debasement and calling for spiritual transcendence. Yet, and to this day, when it comes to motherhood, instinct goes unchallenged is claimed to exists within every woman and girl. Rather than “transcending” it, everyone is keen to preserve, claim, and praise it.

The glorification of motherhood and the sanctification of educating future generations value the role of the mother on the surface. What they effectively do, however, is put in place a system of surveillance to control mothers, backed by a huge number of medical and psychological studies that hold mothers to ideal standards and account them in case of any health or behavioral issue with their children. Even when these transgress and challenge social norms (in their sexual choices, for instance), the mother is to blame. The ideal standards demanded of mothers begin even before procreation, as they are urged her to adopt a healthy lifestyle that does not affect fertility, ingest drugs that increase their chances of pregnancy, prepare themselves psychologically, and educate themselves about pregnancy and childrearing.

It is impossible to miss the huge number of books dedicated to pregnancy, childbirth, and child-rearing that populate libraries’ shelves and that further divide and crystallize gender norms through their interpellation of mothers. The spread of Freudian psychoanalysis contributed greatly to creating the myth of the ideal mother, whereby the mother’s relationship with her child becomes the major event of a human’s first few years of life, and consequently, the main source of mental illness.

Although these publications raise the awareness of mothers considered educated and increase their knowledge about health, they also serve the patriarchal system by burdening them with additional duties when it comes to the physical and psychological health of their children. Children become the focus and center of the family, and are given far more attention than their mother because of the assumption that women now have access to better medical care than their foremothers.

A new stereotype of the ideal mother has been trending for a few years now: the image of the “supermom” has been promoted by the media through their portrayal of mothers who are able to juggle between work, motherhood, and love, and who are always manage to be at the top of their femininity. But the daily reality of working mothers cannot be more different: they have to deal with an economic crisis caused by a nasty capitalist system that does what it can to dissuade women from having children. The obstacles women face under such system are innumerable – delayed promotions, misogynist comments, and psychological pressures of all kinds. Many mothers find staying at home to care for their children after delivery more lucrative, if and when their partner can meet the expenses of living. As for working class women, staying at home becomes a luxury they cannot afford; many have to return to work as soon they can, sometimes without resting enough after giving birth.

The return to nature and the preservation of the environment are used as trends to apply additional pressure on mothers, from painful birth to “natural” breastfeeding. If a woman chooses otherwise, she is attacked and accused of not wanting “the best” for her children, according to an ideology and society that pursue what they deem to be the interests of children, even when those come at the expense of the mother’s and her wishes. The application of such an ideology cannot be reconciled with the lifestyle of working mothers; in fact, if applied at all, it would prevent women from having any private life outside their role as a mother, and turn them into mere reproductive and child-rearing machines. They would be required to spend their entire time caring for their children-turned-deities, breastfeeding them the “natural” way, sleeping at the same time as them, washing cloth diapers, preparing breakfast, and paying attention to the psychological, educational, and pedagogical aspects of their life.

In addition to the enormous pressures the myth ideal motherhood brings about, it also completely erases the role of the father loses grounds when it comes to gender equality and the distribution of parental responsibilities. This discourse brings us back to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, for whom the father exists as an “authority figure.” The mother-child relationship is considered sacred in the first three years of life, which reduces motherhood to a biological bond and women to a reproductive role. As a result, the father is excluded from care work and education; he becomes a mere participation in the fertilization of the egg and remains absent from child care, a responsibility that solely falls on women.

Oftentimes, women are valued through their readiness and ability to become mothers, as per religious, national, or "natural" rules. But women today have the right to refuse to have children; to uphold our right to choose, we must reject the blatant interference of the state and society in our bodies and practices of motherhood, and counter the promotion of ideal motherhood by the media and the medical industry.

- 1. As portrayed in Delacroix’s painting La Liberté guidant le peuple (liberty guiding the people).