Of Periods, Bodies, and Desire: A Discussion on the Erotic Image in Artistic Representations

issue_2_cover_en.jpg

Introduction

Of the three women artists who joined us for in this discussion, all three work in creative fields, but none self-identifies as an artist. Sousou works in the television business; her graduation film was about five women, each having a monologue about women-specific issues. She recently worked on a short video about a young girl going into puberty and dealing with her first period. Sarag works as a librarian; she sometimes paints, and her paintings center bodies, or parts of them, as their main subject. Some of her canvases were exhibited. She also made a personal sketch series that was based on quotes and sayings we hear in our everyday life, and some of these were turned into postcards. Mawn identifies herself as an urban researcher and works heavily with illustrations. She also worked with Sousou on a short illustration awareness video about trans issues.

The discussion session was held at the office of the Arab Foundation for Freedoms and Equality on the 26th of November 2015 and lasted for two and a half hours. This article includes short excerpts of the main ideas that occurred during the first hour and a half only.

When it comes to representation policies, it should be mentioned that the participators are speaking out of their personal experiences and opinions, and they, therefore, do not represent any side or group or association, and are only expressing their own views, even when they speak in plural.

Pseudonyms were used in this discussion to protect the privacy and safety of the participators.

If you would like to suggest an idea for discussion, or even host a discussion with a particular group of people in the “Openings” corner, you may contact the Kohl team at: kohl@gsrc-mena.org.

Rebecca: It is interesting that none of you is willing to identify as an artist, despite your work in fields that are traditionally considered artistic. But all of your work comes from a very private place that is also political. How do you reconcile the two?

Sousou: I once produced a short video about a young girl going into puberty and having her first period. Though its conceptualization relied on focus group discussions, this video felt very familiar to me. I felt I was putting my teenage self on screen: the geek in me was trying to investigate the period taboo to understand it. Creating this video was a travel down memory lane to the time where I was getting my period, I was growing boobs, etc., in an environment that offered no prior information or preparation. At the time, in fact, my femininity came upon me as an inconvenience, as it didn’t go well with my lifestyle. I liked playing football, and the menstrual cycle would interrupt that at times. This was my chance to make peace with what the child-me had to go through alone.

Mawn: As traumatic as that may be, period is by all regards a myth. There is a certain way to behave, and certain behaviors lead to certain results. There are always these statements about how your period will be different once you reach adulthood, once you have sex, once you have children, etc.

Sousou: I believe these myths had their foundations in the past. The basis may be gone now, but we preserved the ritual. Your first period used to be your rite of passage, meaning and declaring that you are now a woman. There used to be economic and social repercussions to this change of status. Life changed, but the rituals remained, and this is where the clash starts. We don’t understand why we are being put through these rituals, but we’re forced to adopt them anyway.

Mawn: I still feel weird asking for pads to be delivered from the local grocery store.

Rebecca: But in some cases, this awkwardness can be used to our advantage. Since men are uncomfortable with the period taboo, a pad in your bag can make security checkpoints faster.

Sousou: I find these details interesting. When we are able to use some disadvantages to our advantage…

Mawn: Well, what about when the taboo turns into a fetish? I was once stopped by a young man in a car. He was pretending to be studying gynecology and conducting academic research about a subject related to women. I had still come back to Lebanon after studying abroad, and was somewhat trusting of people, so I agreed to help him and got into his car. He started asking me seemingly harmless questions, mostly about my period, if I use pads or tampons, if I go to the beach when I have my period, etc. Then at some point the questions started to turn very odd, and that is when I realized he was masturbating!

Sousou: I think I was approached by the same guy, literally! But I didn’t get into his car. I, for one, lived all my life in Lebanon.

Rebecca: Periods are rarely represented artistically, because they are perceived as gross or intimate. As for vaginas and boobs, there is a long tradition of nude painting and representation, but it is interesting to hear the take of feminists on it.

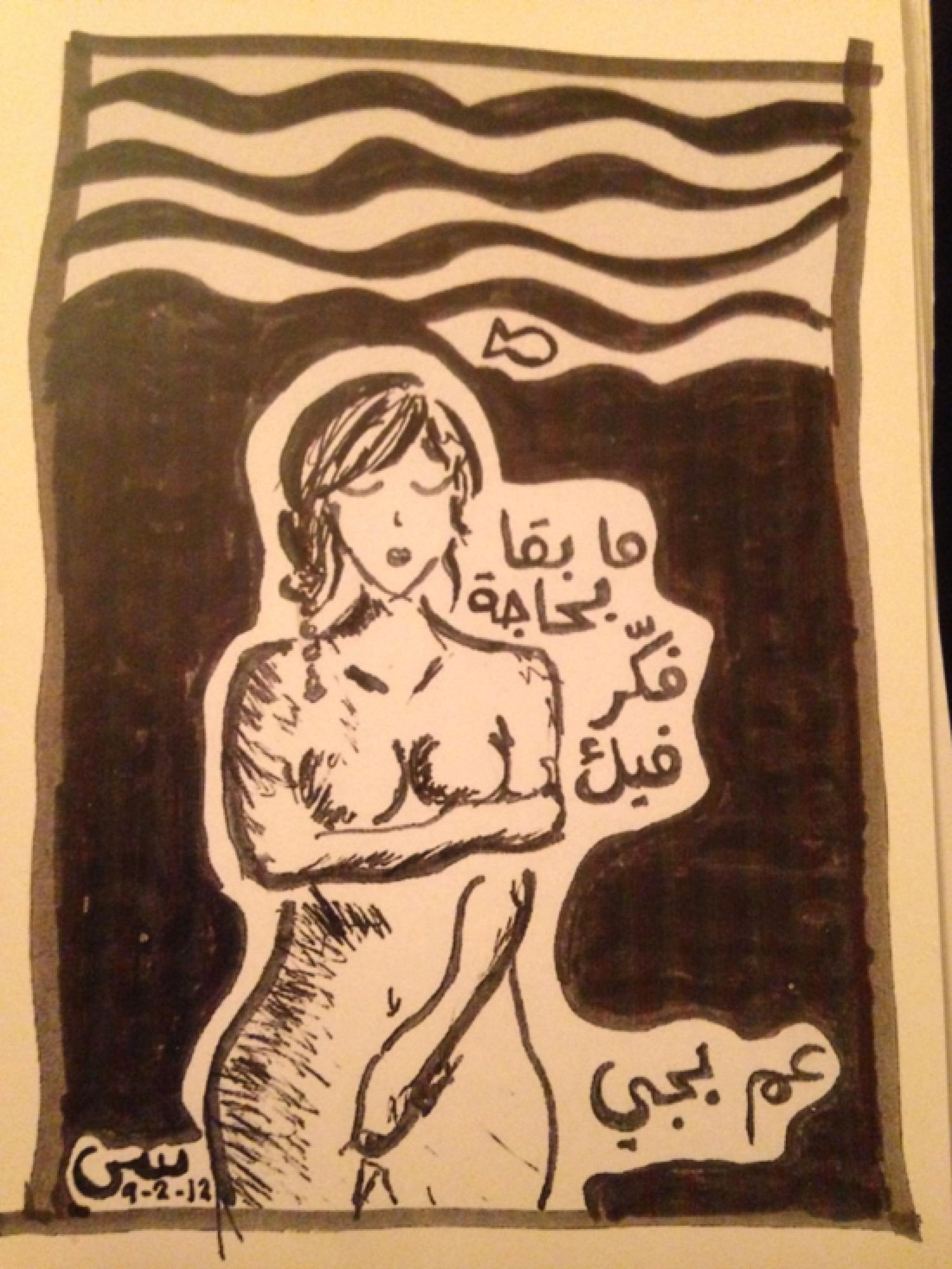

Sarag: I have done a series of drawings that portray vaginas and boobs and others body parts. I think I go through phases, and in each phase, I have a subject that I am focused on.

Rebecca: What I find interesting about that series is that you draw them in a way that is not necessarily conforming to mainstream, acceptable images of bodies, such as, for example, drawing hairy legs.

One of Sarag's postcards

Sarag: Yes, but I don’t think about it this much. I am not very self-conscious about my body hair. As far as I am concerned, it is all a part of me and I am comfortable with it. I don’t necessarily exhibit or emphasize my hair, but I don’t fight it either.

Mawn: What I find interesting about the work that Sarag has done (postcards and paintings) is the fact that it clearly comes from a place of desire. But at the same time, they are not mystifying anything – they are not pornographic either. The choice of details like body hair, or the fact that they are completely naked makes them differently erotic. They trigger desire in a different way. When you see them, you don’t find yourself wondering what is concealed for instance, but it triggers questions because they are taken out of context. They are separate body parts.

Sousou: I find this intriguing. I usually perceive the erotic as within the narrative only. I would like to see how it can be done or perceived without the narrative.

Mawn: I’ve been reading about the “image” lately, especially Benjamin’s work. He talks about the “unruly desire” to know what is behind the image. Then, there is the concept of what slips into the image, but you somehow need to look for it. It makes you want to know more, specifically because it is hidden or unpredictable. On the other hand, in your work, Sarag, the process is the opposite: you hide nothing, but the outcome still goes in the same direction.

Sarag: As I said before, it depends on the “phase” I am going through. One particularly long phase had me drawing ksus1 and bzez2 all the time.

Sousou: So the plural of koss3 is ksus? Or is it an Armenian-Lebanese specificity?

Rebecca: I think that the most common form is kses4…

Sarag: Yes, kses.

Sousou: It might depend on the region you are from.

Rebecca: In all cases, it shows how rarely we use the plural form of it.

Mawn: Maybe kses because it rhymes with bzez…

Rebecca: Back to Sarag’s paintings, I remember she once painted a close-up vagina, with nothing else but the skin, the lips, and the pubic hair.

Sousou: To me this is not at all erotic. For me, it is just a vagina. It is not linked to a person, and therefore it is not linked to desire. In this case, what is hidden (the rest of the body) is not erotic, and therefore the image is not erotic.

Sarag: There cannot be one definition of what makes something erotic. In the end, who gets to decide that an image of a vagina is erotic? Sometimes, a color could spark desire in me. In the case of the collection to which this painting belongs, I didn’t draw it with the intention of making it erotic. In fact, I find it fascinating to see how my feelings and my process transpire to others when they see the painting.

Mawn: But is narrative that important, Sousou? Porn has a narrative, regardless of how good the narrative is.

Sousou: Exactly my point, it works! It’s a stupid narrative, but it works.

Mawn: But does it really work? The plot actually takes up very little space compared to the sex scenes.

Sousou: Imagine the same porn clip without this little introduction. The fantasy itself is important, something that Zizek talked about. If you are in the moment and you lose the fantasy, you will suddenly feel silly. Maybe the privacy also plays a role when you see but you are not seen, for example. Take the movie Persona. There is a scene where one of the character tells another about a sexual encounter she had in the past. In my opinion, that was the most erotic scene on screen I have ever watched, and they don’t show you anything. The whole act is hidden, but what makes it erotic is that it makes you imagine it. Eroticism takes place in your head. This leaves space for additions and subjectivity, thus enhancing it.

Mawn: But the hidden is not the only way to eroticize. I don’t think I have ever addressed these topics in my official/public work.

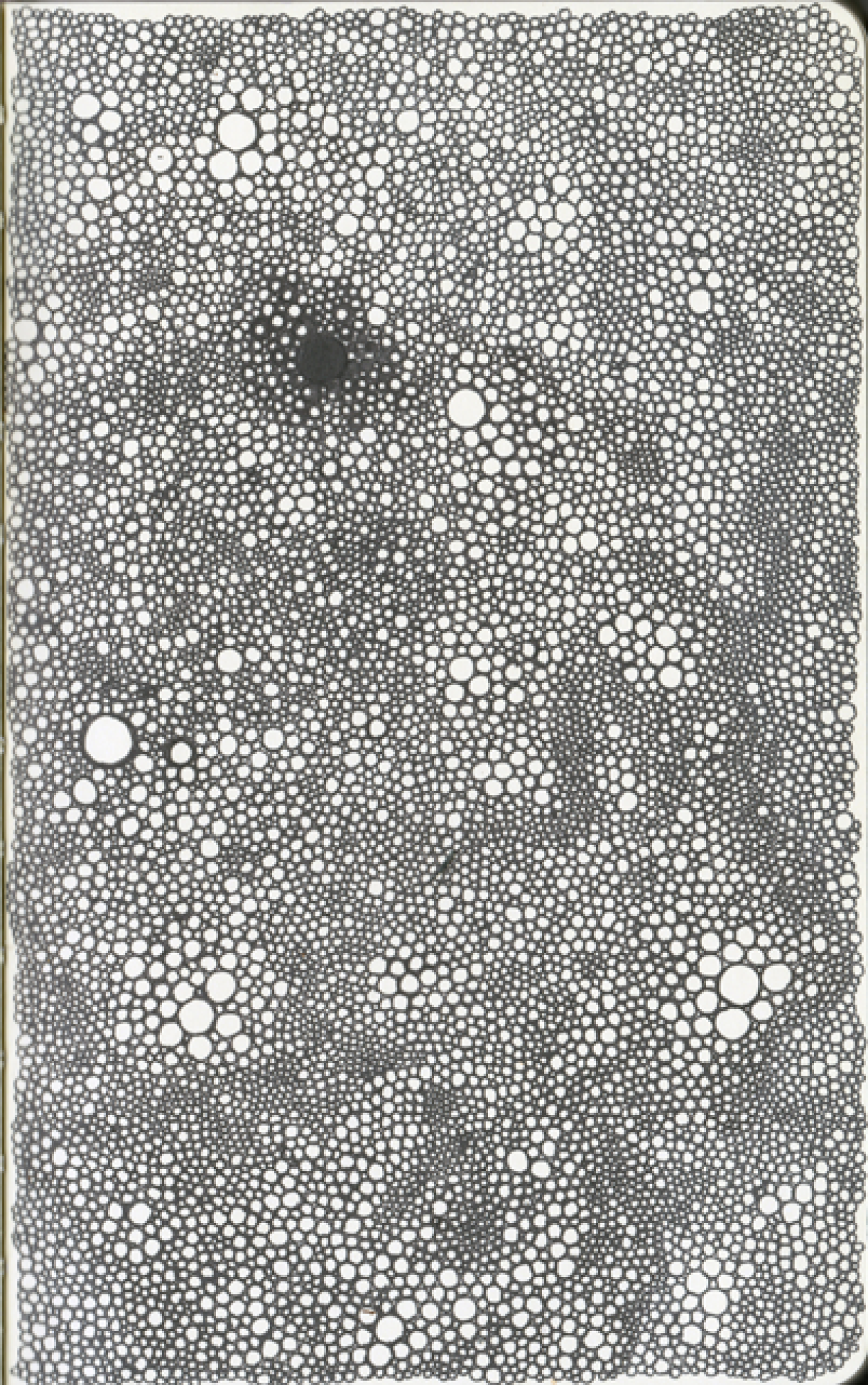

Sarag: I can’t stop thinking about your circles, Mawn. They felt so erotic to me. Sexual organs don’t impose eroticism. Desire can be conveyed by a color, a repetitive shape… It comes from a very personal/subjective point.

Mawn's circles

Mawn: If you think of it, regardless of the subject, when the artwork conveys a certain repetitiveness of compulsiveness… it translates something related to the body and its labor. It becomes the embodiment of something very physical, and for me, this can contain desire. The issue of body was a difficult question when we were conceptualizing the trans video. The issue of how to represent a body without falling into stereotypes was a big dilemma for me. It’s an illustration, it’s supposed to be either symbolic or reductive or simplistic. But then, looking in retrospect at the silhouettes or characters I usually draw, they’re very asexual/agendered. I guess the thought of escaping binary or stereotypical representation was always present in my work, but I hadn’t verbalized/realized it until then.

Rebecca: How do you represent the specificity of a trans person? You’re not trying to draw a man/woman, you are trying to show this man or woman as a transman or a transwoman, and you cannot represent them through their sexual organs because it’s irrelevant to the identity.

Mawn: We tried to address this by shifting representations. It was easier in the video than the pamphlets, but we tried to show people in skirts, binders, different colors, etc.

Sousou: Then there is the trap of generalizing the character so much that you end up dehumanizing them.

Mawn: It actually gets tricky when you are trying to send a message across to an audience. That’s harder than artwork. The function of the representation dictates its level of sensitivity.

Sousou: I agree. Political correctness kills art.

Mawn: I agree to a certain extent. In some cases, being politically correct is a political stand. The issue of representation in this case was heightened by the fact that none of us was a transwoman. Unless you are going through the transition process, you cannot really say that you know what it is like or about. You try to rationalize it or make connections with your experience, but you can’t get it.

Sousou: It was a constant discussion till the end.

Mawn: Yes. Also, if you take the illustration – since I did that individually, not with a team – I kept making drafts and asking myself what could be problematic about each, until I reached the most reasonable or least offensive version.

Rebecca: But even if you identified with the community you are trying to draw, you would still be at risk of generalizing or offending. Then, there is the issue of moving attention away from sexual organs when the physical process is central to many trans individuals.

Mawn: Yes, that was a big debate. We wanted to show or indicate organs as much as possible, and within legally and socially accepted limits. We did insist on showing organs, only to do so without centering the trans identification process around that detail.

Sousou: That’s what I was referring to when it comes to generalizing to the point of dehumanizing. Illustrating is even more difficult than writing. And in spoken/written text, Arabic is even less helpful that other languages.

Rebecca: And how was your art perceived by the general public? What was the feedback you received?

Sousou: The only negative response I ever got on my graduation movie was on the basis that the issue was thoroughly covered. In fact, the person who was critiquing my work didn’t know this was a student project and assumed it was the work of an established/seasoned artist.

Rebecca: Do you consider the topic thoroughly covered?

Sousou: No. I think there are two circles in terms of media production. First you have the mainstream media, where messages and images are traditional, well-rounded, and non-provocative. Then, you have the art scene, where the themes and opinions are more radical, shocking, and provocative. The latter, however, is basically preaching to the convert. Its audience and impact are far more limited. What was that quote, Mawn? A small change in a radical movement…?

Mawn: “A small change in a mainstream movement is more productive than a radical change in a marginal movement.” But, in the end, it depends on the aim of the product you make. Is it social change or personal expression/thought? That is the difference between being an activist or an artist for example. You could be a politically engaged or aware artist, but that is not necessarily activism.