Language at the University of the Poor

Translation edited by Ghiwa Sayegh

transgressive_translations_25

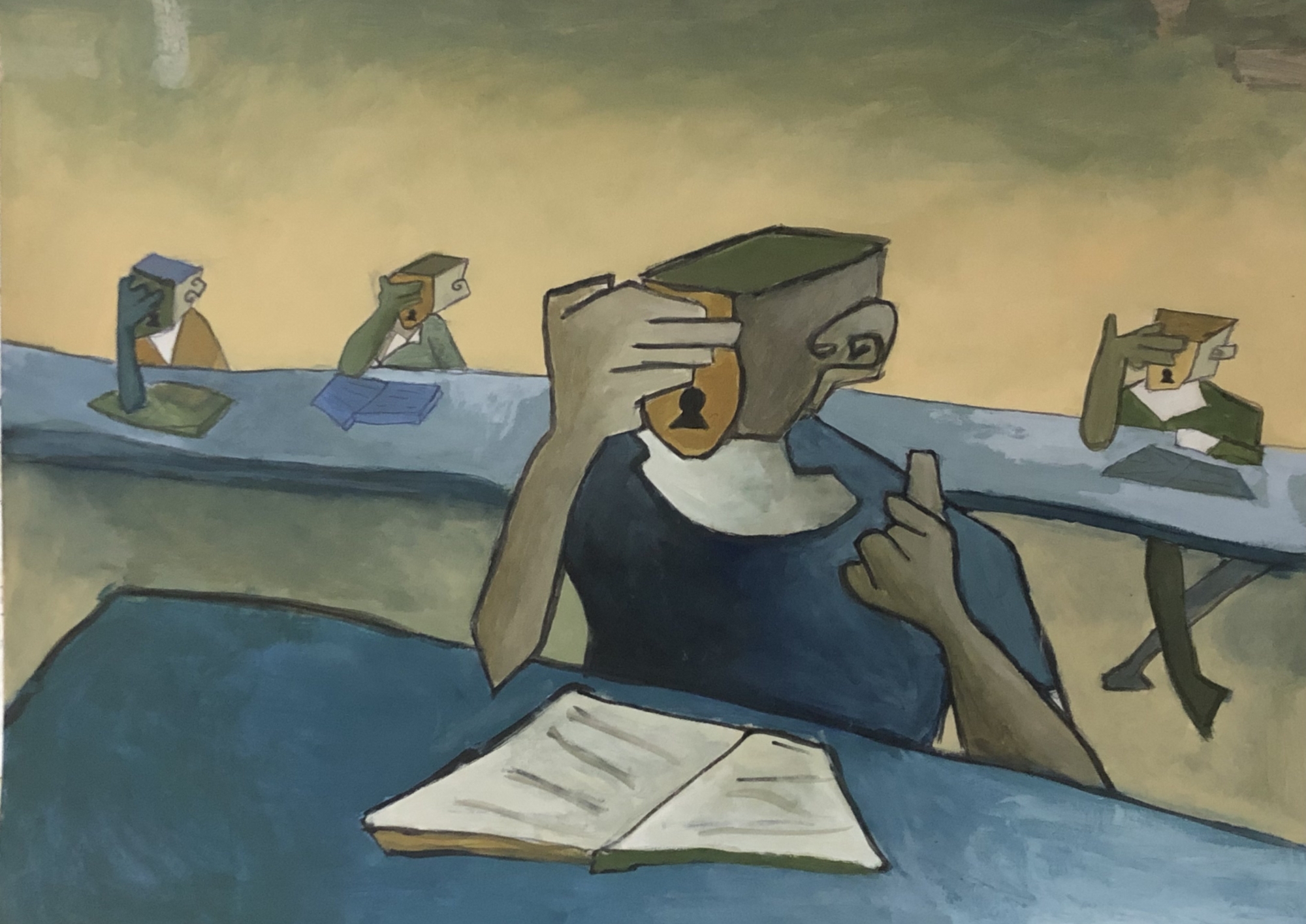

During our second year of on-campus studies at the Lebanese University’s Faculty of Law and Political and Administrative Sciences, we were drowning in a sea of confusion. In a Private Administrative Law course, it dawned on us that the terms “syndicate,” “order,” and “association” did not mean the same thing. We felt or rather sensed, that there was an underlying problem. Our course was handwritten in Arabic on a stack of papers by the professor of the course – whose handwriting was deliberately unreadable for “aesthetic” reasons, as he claimed – and we noticed, among the many words that filled the tight lines, that the word “union” was the single synonym to the three foreign terms. In all honesty, I was then, I continue to be, and it seems that I will unfortunately remain, a freelancer on hourly paid contracts. I was not familiar with the history of the broad global trade union movement in any other language than in Arabic. I was certainly not aware that this huge historical background overflowed with terminologies, and that our abundant revolutionary history had disrupted the bourgeois states that claimed an Arab identity, belonging, passion, honor, fraternity, etc. (unleash nationalistic traits here). Our university professor, who was also an honorary member of a long-standing political party that rooted itself in isolationist practices, did not have enough paper stacks in his curriculum to explain to us these discrepancies. He simply said to us instead, “If you do not know French, learn it. How do you expect to understand Lebanese law or any other law for that matter without language proficiency?” He then proceeded to add to his pile papers (in other words, the course), a footnote that read, “In French law, there is a difference between syndicate and order.” We memorized the verdict – I meant the course; the professor remained in his full-time university position, and we remained lost in our confusion.

What this doctor in law really taught us, especially with the way the course was concluded (may we all be forgiven), was that the nation-state project in the Global South holds our economies hostage, in part by demanding we be linguistically servile. Despite the abundance of different economic classes in that university hall, no wall was moved when it was the bourgeois realism that was taken for granted and imposed on us all, and we were expected to grovel. Never mind that the history of the bourgeoisie itself was shaped by labor struggles, such as the right to strike that was seized by French workers in the nineteenth century, and by revolutionary surges, like the Algerian Liberation War. The popular uprisings of the “Winter of Discontent” also come to mind, which long-standing labor struggle resonated in all the geographies of the British Empire. To go back to our story, these terms and their translations are not mere technicalities; their colonial genealogy forms the very structures of the repressive institution known as the nation-state. The Lebanese University curriculum, in all its aspects, exerts every effort to normalize its eagerness to stay faithful to the source language. In doing so, the Arabic language is at times used, but it is mostly bypassed between parenthesis, in quotes, and in hybrid sentences that, in their quest for academic merit, alienate the working class ranks. The more you hybridize your language, the higher your prestige, and the less chance you have to notice a difference in the translation that links the source (the foreign-colonial) to the target (the students at the University of the Poor and their language). As a result, you remain lost in translation but proud of this so-called “civilized” confusion.

Political and legal studies love the dichotomy between the “original” (or the source) and the target, and so does the patriarchal arrogance that imposes half-dialogues between a professor and his/her students, in an institution concerned with evaluating and taming the “less fortunate” social strata through codified, rigid, and specific knowledge. Following the end of direct administrative and military colonialism (that the national history books of the bourgeoisie call “independence”), this dichotomy was an essential feature in the project of nation-state building, and the public university in most nation-state models (post colonialism) is the product of its ruling class.1 In fact, the academic institution is a symbol of the patriarchal national culture.2 And the irony lies here: universities are established as a tool of top-down violence (in the sense of Foucault and Bourdieu, as far as I know); these same edifices experience grassroots and workers’ uprisings that bring in some reforms, only for them to fall back into the hands of (neo)liberals, and the cycle repeats itself. But the Lebanese University’s story is a rare one: workers had an anticipatory plan and formed an alliance – which does not have the slightest hope of being reproduced in the Lebanese context today – with sections of students who worked to understand the reality of their colonial identity combined with its class dimension. So, they revolted against the colonial institutions of higher education, where the comprador of the country was dwelling in peace, wealth, and honor. The Lebanese University was the result of a labor struggle that began in the halls of the Teachers’ House in the fifties of the last century and ended up in fierce and militarized confrontations in the streets of the capital. Those confrontations led to a state of confusion within the Lebanese and French authorities and resulted in the official recognition of the University by the bourgeois authorities (the bourgeois class – let us agree – are themselves the ruling authority) in 1961.3 However, this university’s project was revolutionary right from the start as it carried with it a discourse that combines class struggle and liberation from colonialism. This revolutionary vision demanded subjects are taught in Arabic, especially those related to politics, law, and history, monopolized at the time (and still are to a certain extent) by English-speaking and French-speaking people in Lebanon. This demand was most denounced by the ruling authority and its French forefathers, who ended up recognizing the university as that of the workers’ and poor people’s by inaugurating a French branch to the Faculty of Law (Filiere E.D.D). It is that same branch where representatives of the “civilized” Lebanese bourgeoisie are enrolled nowadays. That the monstrous foundations of the nation-state were taught as a subject in the logic of a language that most people would understand, was driving the ruling authorities mad. However, the frenzy did not stop at this point. The masses of workers and students demanded that French and English be taught, as a second language, free of charge, to members of the economically vulnerable social classes. Indeed, at the height of its liberation discourse, the Lebanese University was engaged in a linguistic struggle, or perhaps a struggle to bolster a language that would challenge the daily class oppression and cultural exclusion, both rampant in the context of the bourgeois independence carnival.

To avoid embarrassing any colleague at the Lebanese University who may inadvertently stumble upon the title of this article, I would like to reiterate that the story of the Lebanese University is quite different from that of any other public university; it started from within the ranks of workers. After the predatory rise of the finance, reconstruction, and new banking engineering policies, led by successive governments and parliaments since 1989, the University of the Poor returned to its assigned position within the "normal" capitalist path of any educational institution: it was once again in the grip of the parties in power, the values and ethics of its staunch, renewed bourgeoisie, and its long-held “American Dream.” The University of the Poor turned into a “homeland” university, with what patriotism means in terms of male repression, class bias, and colonial prevarication.

Is talking about the history of the linguistic struggle of the largest university in the Lebanese entity a cognitive luxury? Of course not. On the contrary, our confusion between the word “syndicate” and the term “union,” and our financially engineered and intended ignorance of what the difference between a professional union and a labor union means, is indispensable for understanding the alliances and absurd fronts that formed post 2019 uprising. Take for instance the union uprisings,4 the alliance between the Drabzeen Initiative5 and the National Coalition,6 the dispersal within the ranks of “Mihanyeen and Mihniyat”7 or LebProAssociation, and many other temporary and ideologically unstable formations led by the upper middle class and petty bourgeoisie (such as Lihaqqi8), along with the exploits of secular clubs, the fluidity of student alliances, and the gradual and continuous decline of the opposition discourse within the Lebanese University students ranks (e.g. the Lebanese University Students Bloc9). They all had a discourse that essentially and deceptively clings to the assumed presence of an intersecting interests between the petty-bourgeoisie and the middle class from one side, and the workers from the other. The emergence of such a discourse is neither random nor new; it is the result of an organized linguistic policy which ultimate goal is to silence the workers (most of whom are not citizens to start with), by including them in the bourgeois discourse, out of love, voluntarily and coercively at the same time. Language and discourse are political formations that stem from and reorganize reality. In this regard, we say, no secular speech can eradicate class oppression, just as the electoral bourgeois alliance’s speech cannot represent workers’ sufferings even if they attribute unionist labels to themselves.

I conclude by saying that language is the space in which all frontlines of our ongoing battles reside, making our fight within and around its spacious realms ineludible.

- 1. An example of that is the history of the University of Jordan, the University of Damascus, and Cairo University in their inception, before and after the popular protests starting the 1900s.

- 2. In this case, Frantz Fanon (1967), June Jordan (1982), James Baldwin (1963), and bell hooks (1994) would agree with me. Patrice Lumumba may attest to that as well.

- 3. See Emile Shaheen (2011) and Imad Zoghbi (2002); you may also check the archives of Assafir newspaper and/or the archives of the student movement in the public library (if you are lucky to find it open). For a dose of dark humor, see (or don’t) former minister Hamid Franjieh's dreams of a Lebanese University “worthy” of the position of the Lebanese bourgeoisie among nations and imperialisms.

- 4. "The Syndicate Is Rising" is a coalition that includes many activist groups that emerged and coalesced during the October uprising, aiming, as they announce, to "strengthen union work, present an alternative program, and reach decision-making positions in the Engineers Syndicate." (Arabic editor)

- 5. The initiative “Drabzeen of October 17” is one of the blocs that arose in the context of the October uprising, and it is, as it defines itself, “a network of dozens of groups coming from political spaces, regions, professions, and specialized groups that worked or were established during the ongoing uprising until today.” (Arabic editor)

- 6. “National Alliance” is "a political organization that aspires to rebuild a sovereign, pluralistic, democratic, and just citizenship-based state." (Arabic editor)

- 7. An association born in the context of the October uprising and that includes female and male workers in different sectors. It is active within the framework of "confronting the ruling class," as it claims. (Arabic editor)

- 8. “My Right/ LiHaqqi” is, as it defines itself, “a social-political organization committed to being fully aligned with people and rights, and adopting horizontal organization, decentralization and participatory democracy.” It is one of the organizations that arose in the shadow of the October uprising. (Arabic editor)

- 9. The “Lebanese University Students’ Bloc” describes itself as “an independent national student group comprising students and graduates of the Lebanese University from all branches and faculties. It is concerned with the issues of the university’s people and students in particular, from all social groups, especially the most marginalized, with their academic, material and moral rights, seeking the formation of a productive, independent national university and a just society” (quoting from the respective organizations’ pages and not an endorsement of the descriptions). (Arabic editor)

Baldwin, James. “A Talk to Teachers.” The Saturday Review, December 21, 1963.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skins, White Masks. Translated by Charles Lam Markmann. New York: Grove Press, 1967 [1952].

hooks, bell. Teaching to transgress: education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Jordan, June. “Moving Towards Home.” Poem. 1982. https://20thcenturyprotestpoetry.wordpress.com/2013/10/30/june-jordans-m...

إميل شاهين. الجامعة اللبنانية ثمرة نضال الطلاب والأساتذة. دار الفارابي، 2011.

عماد الزغبي. الحركة الطلابية في لبنان: خمسون عاما من النضال ١٩٥١-٢٠٠١. مؤسسة دار الكتاب الحديث، 2002.