The Woman with a Scar

Cover Website.jpg

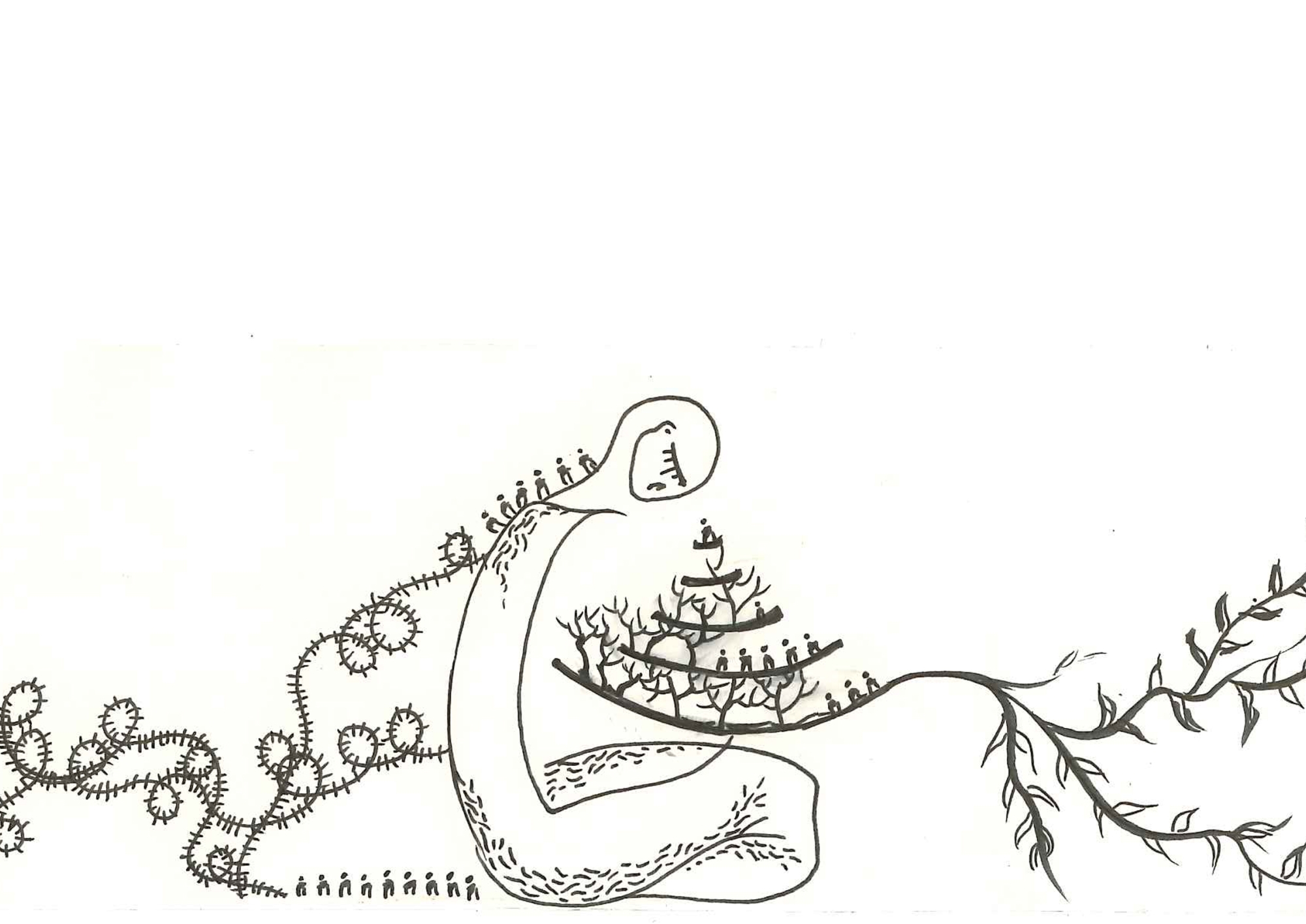

Illustration by Zeina Hamady 2018 ©

The scar was big. So big that it stretched from hip to hip, dividing Mariem's abdomen into two, like the path that parted the sea for the Israelites.

Mariem folded her jeans and put them on the wooden stool next to the examination table, then took off her knickers and placed them on top of the jeans. Very quickly, she turned toward the nurse to avoid catching a glimpse of her reflection in a big mirror opposite her. The nurse gave her an apron-like garment, which she tied around her waist.

She thought how strange it was that nobody could see the scar.

“It's all in your imagination,” they sometimes said, or “stop thinking about it, and you will cease to see it,” or “what scar?”

People were either blind, or they pretended to be. Even when she was not looking at it, it was hard to ignore it when it burned with a throbbing pain, which got so intense that it whisked the air out of her lungs and prevented her from sleeping on certain nights.

Mariem climbed on the examination table, spread her legs wide open as the nurse instructed her to do, and waited.

The doctor walked into the room briskly. His movements were fast and mechanical. He sat opposite her, but he didn't look at her face. For now, she was nonexistent, and his attention was entirely focused on the narrow, dark space between her legs, the gate to the magical realm that produces babies, which the doctor looked so eager to explore and probe until all of its secrets were known to him. His face was a mask of stone; behind tortoise-rimmed glasses, his eyes were cold and glassy. Today, a job had to be done, and everything about him said that he was the one for the job. Mariem looked at the ceiling.

She felt the coldness of the speculum as it took hold of the skin and moved her muscles apart with icy determination. She kept her eyes focused on the ceiling. Something slithered inside her, something cold and slick like a snake. Only, this thing was hard. It didn't hurt, but the invasiveness was difficult to ignore. Mariem flinched and tried not to let the doctor or his nurse sense her discomfort. She only had to focus on something else, and the ordeal would be over before she knew.

“You're tense, try to relax,” the doctor said tersely.

But she is trying, can't you see?, screamed a voice inside Mariem's head. Mariem ignored the voice and tried to relax. But the more she tried, the more tense she got. The doctor let out a tired sigh, and continued doing what he was doing in silence.

What would have Dada thought about this? Dada was a midwife. She never let a male doctor put a stethoscope on her chest, let alone look at her womanhood. What would she have said if she saw Mariem, one of her granddaughters, lying flat on her back with a man peering between her legs?

When it came to childbearing, Dada never trusted doctors, or medicine for that matter. She gave birth to nine children, six of whom survived to adulthood, and helped hundreds of women give birth to hundreds of babies over the forty years of her life that she spent in birthing rooms. She believed in the duty of populating the earth as God commanded Adam to do, and Adam did as he was bid. Now that the earth was full, God fell silent, and Mariem was full of questions.

There was a buzzing in the room, a fly, perhaps, or maybe it came from Mariem's head. From the corner of her eye, she caught sight of the nurse trying to suppress a yawn then looking at her watch. Above the nurse's head was a large framed picture of a toddler with milky white skin, blue eyes, and a large, toothless smile. Why pictures of babies in gynecologists' cabins were always white and blue-eyed was a mystery beyond Mariem's understanding. Beside the picture, another big frame enclosed a verse from Surah Maryam, written in golden calligraphy. “And mention, in the Book, the story of Maryam, when she withdrew from her family to a place toward the east,” it said. Mariem tried to think of a link between the verse and the baby's picture, but could find none.

The doctor pulled the speculum out, took his gloves off, and walked to his desk. Mariem let out a discreet sigh of relief. She put on her clothes and followed the doctor to his desk.

“Everything is fine,” he said. “You've recovered fully from your last pregnancy. It's safe for you to conceive again.”

He scribbled something on a tiny piece of paper and handed it to Mariem.

“Your ovaries are sluggish, but it's normal for a woman of your age. These medicines will help boost your fertility.”

Mariem folded the paper and slid it in her bag with a swift, mechanical gesture. She had never asked him for something to boost her fertility, but she thanked him all the same. She had been seeing this doctor for nine years with the hope to conceive, but in the last few months, she had been coming here for her post-cesarean follow-up. Today, he had looked at her biological clock and decided that it was time for her to conceive.

Mariem walked slowly to the door, but she did not really want to leave, not quite. Something wanted to be said, and the words were there, wedged in her throat, waiting to come out.

The moment she opened the door, the noise in the waiting room flooded the doctor's office. Mariem froze for a few seconds, and the words finally came out – more like spurted out of her mouth, really.

“I don’t want another baby,” a voice said. Mariem was startled. The doctor and the nurse were startled too. Even the noise of patients in the waiting suddenly died out.

The doctor’s eyes were on Mariem now, examining her intently as if he was seeing her for the first time in his life. Mariem, who had just said the unimaginable, was overtaken by discomfort, and was about to flee the scene of her disgrace as quickly as possible when the doctor's voice caught her.

“Wait, Mariem.”

This was the first time he had called her by her first name, instead of the usual Madame Chelby. Hope fluttered in Mariem's heart.

The doctor closed the door separating his office from the waiting room, blocking out noise and twenty or so pairs of inquisitive eyes. His face was grim, as if he was about to divulge an important secret. From the other side of the room, the nurse stopped what she doing and strained her ears to hear what the doctor was about to say.

The doctor's face leaned close to Mariem's, and she felt his breath on her face, a minty, sterilized breath.

“What I am going to say now, I am not going to say as a doctor, but as a father, or a brother.”

Mariem's face fell instantly. His words did not bode well.

“I know you are still traumatized from your first pregnancy, but I've seen many women like you, women going through difficult pregnancies, then difficult births, only to lose the child afterwards. It’s more common than you think.”

The doctor took a breath and put a hand on Mariem's shoulder. His hand felt heavy and she recoiled instinctively, but he didn't seem to notice her withdrawal.

“But once a second child comes, it's different. Trust me,” the doctor continued. “Give a second child a chance, and give your husband a chance.”

****

The bus stopped and let off a strident hydraulic sound when the doors spread open. A dozen of passengers scrambled hurriedly toward the back door and started forcing their way in. A woman's purse fell in the crowd and she shrieked. Some men cussed. Mariem pushed her way in and stood at the back of the bus. Buildings, people, and cars filing past the window of the bus gave her a sense of comfort. The day was overcast, and the sky was dark grey. The doctor's words played inside her head.

“Give a second child a chance.”

“Give your husband a chance.”

“Trust me.”

But why would Mariem trust him? What did he, for all his education, know about child loss? What did he know about the scar?

The bus driver braked suddenly and the bus jolted. Some passengers lost their balance and fell. One of them dropped a bag of oranges and tangerines, and fruits rolled all over the floor of the bus. Some tangerines got squashed under the feet of passengers, and the sweet smell of wasted fruits filled the enclosed space.

The aroma filled Mariem with an incomprehensible sadness. Anger and resentment – at the doctor? At herself? – rose in her throat like bile. But what could she have done? She was as helpless as those tangerines whenever the Other Woman decided to speak. Mariem dreaded her. She was fearless and had no notion of consequences. I must learn how to control her, Mariem thought, but the Other Woman burst out laughing just as the thought of anyone controlling her crossed Mariem's mind.

There was a time when it might have been possible to shun her, uproot her, nip her in the bud. But the Other Woman came when Mariem was most defenseless, as if she preyed on her very weakness. The first time she heard the whispers, Mariem was in the maternity ward at the hospital, next to a dozen other women in the throes of labor, all of them waiting for God's Miracle, as Dada called it, to come out. Mariem waited too, and didn't give the whispers much thought.

God's miracle did announce its arrival as one by one, babies came out, flailing their tiny limbs, filling the room with rasping wails, while Mariem waited. At some point, a group of young doctors who looked like interns flocked together inside the room. They looked at each woman separately, and when they reached Mariem, they stared at the space between her legs with impassive faces. She thought they stood there a bit too long, perhaps more than they should have, but she could not be too bothered with that. She was incapable of feeling shame or humiliation that day, as the pain threw a thick veil over any sense of pride.

She imagined her husband outside smoking with frenzy, picking fights with nurses, and asking doctors if the baby was going to be fine. Medical staff were walking in and out of the room very quickly, and nobody had the time to say a coherent sentence. There seemed to be a language of secret gestures, muffled sounds, and coded phrases between doctors and nurses that entirely escaped Mariem's understanding. She wished anyone would say something to her, anything. Once, a doctor examined her quickly and said, “it's not time for this one yet,” then walked away without even looking at her face.

Around the early evening, the pain subsided by a notch, and Mariem managed to drift in and out of a light slumber. Then, she started hearing the whispers again, more clearly this time. Whenever Mariem opened her eyes, the whispers would disappear, but would return when she closed them again. Was someone playing a game with her?

Sometimes, Mariem dreamed. She dreamed of that day in the seaside resort, many years ago, when the hands of her husband were clamped around her neck, until someone came to her rescue. Yet in the dream, nobody rescued her, and the hands remained clasped around her neck indefinitely, squeezing the breath out of her, until she woke up drenched in sweat.

Then, she had a feeling of being lifted off her bed, and carted hurriedly out of that busy, noisy room. When she opened her eyes, she was suddenly aware of the blaring lights above her head, of a poignant chemical whiff, of needles piercing her arm.

“Where am I?” she asked in a tired, croaky voice.

“Shush,” a nurse said. “You're being prepared for a caesarean.”

****

The baby is dead.

Mariem did not remember who broke the news to her. All she remembered was that when she woke up the morning after the surgery, it was over.

She wanted someone she could speak and ask questions to, but in that hospital room, she knew no one. Even her husband was nowhere in sight. A young doctor with a kind face came in the afternoon and examined her. She gave her an answer.

“Your baby was in a breech position, and the umbilical cord was circling his neck. They tried to save him, but it was too late. I am sorry for your loss.”

For two days, Mariem lay recovering in a room with two other women. Amal, 19, stillbirth. She was energetic, slight-framed, and thin like a bamboo cane, and she couldn't stop talking about the future babies she will have. Najoua, 32, another stillbirth, already mother to three children. She was plum, extremely light skinned with small grey eyes, and she oozed with fertility. It was as if they had placed them togetherin one room on purpose, to differentiate them from other outcasts –mothers who failed their duty to society, losers

Two days later, it was not her husband, but her brother who showed up. He inquired briefly about her health, and asked her to sign a warrant allowing him to take care of the baby’s body. On that fateful night, she learned, her husband had hit a doctor and broken his nose. He was now detained and awaiting trial. “And Mariem, you have to be careful when they release him,” her brother said. “He can't stop talking about taking his revenge on you.”

But the worst has happened, Mariem thought, and what he could do was the least of her concerns. After her brother left, a crushing emptiness settled over Mariem like a lead blanket. Those sensations she had once experienced when the baby kicked inside of her, the warmth, the sense of safety born out of this two-ness that she had never experienced before, were all behind her now.

That night, Mariem was awoken in the middle in the night by the feeling that something heavy was placed on top of her. She saw a dark shadow crouching on her belly, looking straight at her with eyes red like coals that glowed in the dark. Petrified, Mariem shut her eyes tight. She tried to recite Ayat al-Kursi, but she could not remember the words. For a long time, she kept her eyes shut, hoping that the thing, whatever is was, would disappear if she just ignored it. When she finally opened her eyes again, it had indeed disappeared. Only silence and the darkness of the room stared back at her.

Then, she heard her. It was a muffled laughter at first, then it got louder and louder. Since that day, that was how the Other Woman announced her presence.

Where she came from, Mariem couldn't tell. She was insolent, loud, and she spoke her mind with a hideous insistence. She terrified Mariem because she spoke with such clarity and perseverance when no woman should be able to speak like that. She did not know when the Other Woman would suddenly appear or what she would say, and she did not know what she wanted from her.

Mariem learned to ignore her, sometimes pretend like she did not exist. Yet, for all her cautiousness, she was afraid that one day, the Other Woman would break the thin veil which, until then, had kept her hidden from other people. She was afraid that one day, not only Mariem, but everybody else would hear her.

Today, when she was at the doctor's, Mariem saw what the other woman was capable of. She saw the shock on the doctor's face, she saw how a whole room full of pregnant women or women hoping to become pregnant looked at her. She saw how, in one moment, she could become estranged and lonely – one woman against a doctor and a nurse, one woman against a waiting room, one woman against the whole world. That was how dangerous the Other Woman was.

*****

Mariem opened the door of her apartment and stepped into the darkness. The lights were off and the curtains were drawn. Beware, said the other woman who, at times, acted like a friend or an accomplice, giving her warnings. She was right.

A smell, which Mariem knew too well, hovered in the room. One little step and Mariem stumbled onto something. She put the lights on and stared at the cylindrical object in disbelief. It was a can of beer. A few more cans were scattered around the room.

Further in the corner of the room, he was there, lying on the couch, rubbing his eyes, awakening from a slumber which Mariem had inopportunely interrupted. She almost shrieked.

“Where have you been all this time?” he asked casually, his voice thick with sleep, as if he hadn't been absent for ten months.

“I was at work,” was all Mariem could say. She tried to keep her voice steady.

“All this fucking time?” he grumbled.

“There were no buses,” she lied. “A strike. I had to walk.”

When reality sank in, she took the time to contemplate him. He had lost a few kilos. There was a weathered look about him. His face was pale and drawn, and his thin mustache seemed to have acquired some girth.

He seized another can of beer and cracked it open. He took a long gulp, then, suddenly and unexpectedly, he threw the can against the wall. Mariem's heart jolted inside her ribcage.

“I see you've not been wasting time in my absence. Fooling around like the bitch you are.”

Mariem was lost for words. She had forgotten how she was supposed to act or what she was supposed to say in the face of these outbursts.

Slowly, he rose from the couch. Mariem’s heart started pounding violently. It took him a few moments to steady his balance. She realized then how much weight he had lost. He looked as though he stooped, or became shorter.

“I must have known that my mother was right about you all the way,” he continued, walking toward her unsteadily. Mariem backed off in small steps.

“She said you were bad luck. A good for nothing. One of those factory bitches in heat all year long. But I was a fool not to believe her.”

Mariem's back hit the old wooden cabin. She reached behind her back and felt for something to grab, something that might save her. Finally, her fingers found a hard, smooth object. It was the porcelain unicorn that she had bought at the flea market three years ago. She knew what it was because only last year, he had broken all her porcelain menagerie, and she had managed to save this one piece. She could recognize the texture of its sharp horn. A thought flashed in her mind.

“And look where I am now,” he continued. “Lost a son, lost my job, lost years of my life. All because of you. Whore!”

Mariem's fingers were firmly clasped around the small object. Her eyes were fixed on the floor, but she was aware of his every move. She imagined his contorted face, and in her mind’s eyes, she saw his arms extended toward her. His voice, shouting “whore, whore!” hailed down on her like hammers. If only he shut up, she would yield to his blows and slaps without complaint. Why was it that words continued to hurt after all these years?

Because you're not dead yet! The Other Woman shouted.

Mariem's fingers were wound tight around the unicorn. One strike and her tormentor would cease to exist. Her eyes were closed, but every nerve of her body was in a heightened state of wakefulness and energy. The pain from the scar throbbed with intensity, as if it was about to burst. Then, in the middle of it all, came a thud. Mariem opened her eyes and stared in disbelief at her husband on the floor, lying in a torpor of drunkenness.

Soon, he started snoring, as if in a peaceful slumber. His facial features had softened into a serene look, reminiscent of the times when he told jokes and people laughed. He used to make people laugh with such ease, as if he had been born for that sole purpose. But somewhere along their life together, he had simply lost it. What a sad thing for a man, Mariem thought, to lose the only gift he was born with.

Her fingers loosened their grip, but she did not let go of the unicorn. She tiptoed around him, careful not to wake him, and went into the bedroom. She closed the door quietly behind her, and sat on her bed, exhausted.

What now?

“Oh, let me be!” Mariem shouted with a croaky, trembling voice.

What idiot thinks they can kill another human being with a tiny porcelain unicorn?

Mariem looked at the small object in the palm in her hand, then all of a sudden, she threw it with force. The unicorn hit the window frame and disintegrated into pieces. Taken aback by what she had done, Mariem stared at the white shards scattered below the window. She waited for a sound to come from the living room, but there was only silence.

She took off her coat and her shoes and lay down in the bed.

Yes, vent off your anger, then lull yourself to sleep, the Other Woman said. What man doesn't like a woman who refuses to remember?

“You're a cruel bitch,” Mariem murmured.

You're a coward bitch, the Other Woman replied.

Mariem closed her eyes in the half darkness. Her fingers slid down her belly and lingered above the scar. It still burned. The baby that she had never seen was still etched in that scar. He had no name, and she had no time to mourn him. They buried him hurriedly in an unmarked grave like he was weld h'ram, a baby born out of wedlock. She had wanted that baby more than anything, though she had wanted him for others, never for herself. Once he was gone, the sadness was all hers. Now that that the small thread was broken, she felt like she would never recover from that thin, sharp fracture running through her, dividing her into two women. This, the brokenness, the lame struggle to become whole again, nobody shared it with her, and nobody told her how to walk through it. She felt warm tears trickling down her temples. She cried in silent, violent sobs, and her chest shook uncontrollably.

Outside, the rain was pattering on the window with a sweet, lulling sound. At the other side of the room, the Other Woman was collecting the shards of the broken unicorn and singing.